Historical Model and Colonial History

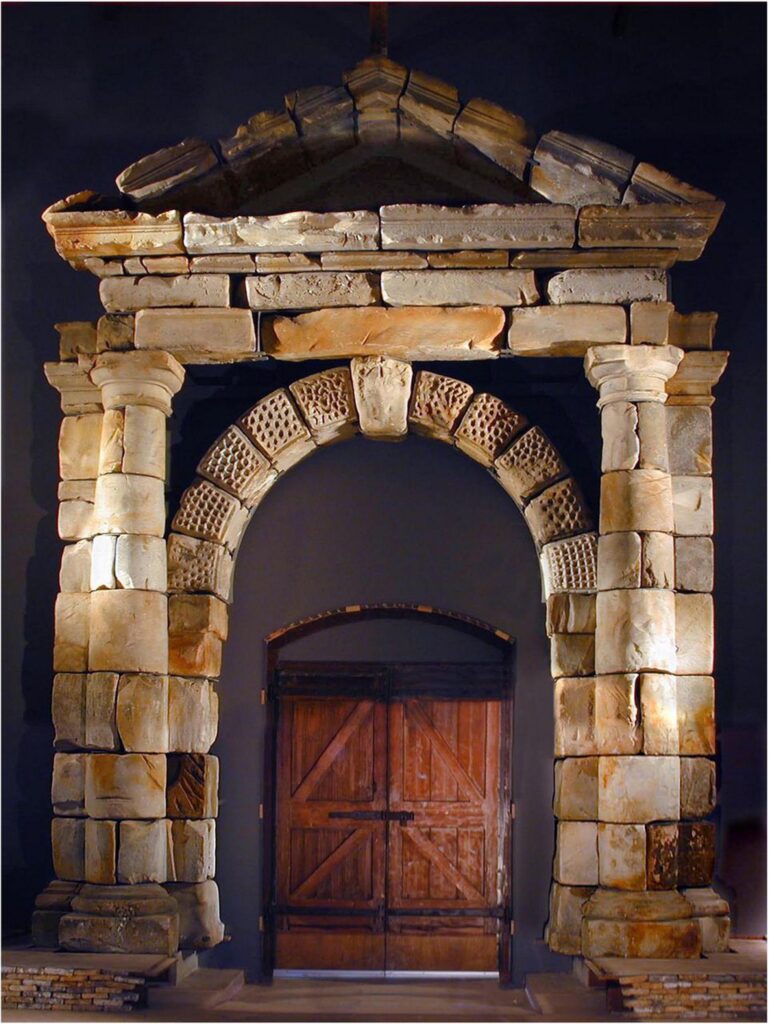

In 1628, a sandstone portal was commissioned in Amsterdam. Three months later, the portal’s components were shipped to the East Indies. The portal was intended for use as a decorative element in the sea-side entrance gate of the Batavia fortress on the island of Java. Batavia was established in 1619 by the Dutch East India Company (VOC for short) under Governor General Jan Pieterzoon Coen, as the capital of the Dutch East Indies for the VOC, becoming the VOC’s most important base for military operations, colonialism and trade in Asia. The city was built on the ruins of the earlier indigenous city Jayakarta. In order to destroy Jayakarta and establish their new headquarters in its place, the VOC had earlier provoked a conflict with the local rulers. Coen subsequently ordered all local people to be labelled as Javanese, expelling them from the location and immediately establishing a fortress and a planned city built based on the contemporaneous Dutch model. Over half of Batavia’s then population consisted of enslaved people. Other Batavia inhabitants included labourers from the Moluccas and Bali, Chinese traders and a small Dutch elite. The VOC attempted to consolidate its position in the region, continually expanding Batavia’s military facilities. It was in this context that the sandstone portal for the fortress was ordered. The portal was intended to symbolise the aspirational cultural and military dominance of the Dutch.

The sandstone for the portal evidently came from the County of Bentheim, and was subsequently worked by stonemasons in Amsterdam before being loaded onto the VOC ship Batavia, which set sail in 1628. At that time, the VOC was already regularly sailing to the East Indies, with many of the sailors and soldiers on board VOC ships coming from the County of Bentheim and surrounding regions. For these people, the VOC offered a gateway to the wider world. People from all social classes joined the VOC, testifying to the extent of the VOC’s international network, a network which enabled the VOC to maintain its trade routes over an extended period.

On 4 June 1629, the Batavia was wrecked off the coast of Australia and sank, resulting in the portal failing to reach its intended destination of Batavia. The Batavia wreck remained on the sea floor, undisturbed by human hands until, between 1970 and 1974, various items began to be salvaged from the wreck site by archaeologists associated with the West Australian Museum. These included timbers from the Batavia’s port side stern, and the stones comprising the originally envisaged Batavia portal.

The telling of the history of this structure serves multiple purposes, including the intention to stimulate a critical examination of historical oppression and colonial exploitation. At the same time, the portal functions as a “strong symbol of understanding between people with different cultural backgrounds” into the future (quote from the greeting of the Indonesian Embassy read at the opening of the replica).